Forward

This post is part of my research for a master’s thesis, which I am releasing early to stress test the arguments, incorporating and citing feedback. Any constructive criticism is greatly appreciated.

Abstract

‘Utility tokens’ are a form of cryptoasset that serve as an exclusive medium of exchange on a protocol which supplies a specific utility (‘utility protocol’). Approaches to value these utility tokens have been put forwards, often using the equation of exchange in combination with discounting to determine a value. Nonetheless, the explanation for the discount rate in these approaches is incomplete. A candidate explanation for discounting is articulated, using Piero Sraffa’s concept of ‘own-rates’ of interest–a concept which has already been put to use on bitcoin.

1. Background

In the wake of Satoshi Nakamoto and the invention of Bitcoin, a new form of digital asset–‘utility tokens’–have been generated. Like bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, utility tokens exist on blockchains or distributed ledgers, which ensure their scarcity and do not rely on a trusted intermediary. Unlike bitcoin, utility tokens are built into a ‘utility protocol’ where they are used as an exclusive medium of exchange for a specific utility on this protocol. These tokens have been the subject of a lot of media, economic, and regulatory attention.

Approaches have been put forwards to fundamentally value these utility tokens using a modified version of the equation of exchange (), notably in Burniske (2017), Winton (2017), and Evans (2018). An argument has also been put forwards and articulated, using the equation of exchange, to point out that these tokens may suffer from a low value due to a high velocity, notably by Buterin (2017), Pfeffer (2017), Samani (2017), and Evans (2018). Samani (2017) additionally suggested that there are some potential mechanisms which could bound high velocities from rendering utility tokens worthless. This piece does not approach this velocity question, and thus may be primarily theoretical with regards to utility tokens–though the concepts investigated can be extended to any asset with a spot and futures market, as will be seen.

Nonetheless, in existing conceptions of utility token valuation the explanation for discounting is incomplete. Following a debate among economists in the 1930s on money and interest, an explanation for utility and token discount rates is articulated, building upon Sraffa’s (1932a) concept of ‘own-rates’ of interest. Sraffa’s concept has already been used to investigate bitcoin interest rates, by Pelham Smithers Associates (2017) and Mukherjee (2017). The next section follows a discussion which forms the basis for valuing utility tokens around a discount rate grounded in market prices.

2. A 1930s Debate on Money and Interest

In the 1930s, there was a discussion between a number of economists on money, interest, and monetary policy. In his 1932 review of Hayek’s Prices and Production, Sraffa takes issue with Hayek’s explanation of the relationship between money and the interest rate (Sraffa 1932a, 49). Hayek argues that a monetary economy is unique in that the “actual” rate of interest can be divorced from an “equilibrium or natural” interest rate because the quantity of money can be manipulated by banks, while Sraffa argues that a non-monetary economy could have as many “natural” interest rates as it does commodities, none of which need to be an “equilibrium” rate (Hayek 1967 (1931), 23; Sraffa 1932a, 49). In Sraffa’s rejoinder, the significance of this point is emphasized, as Sraffa points out Hayek’s argument in Prices and Production that banks’ interest rates on loans should equal the “natural” rate; however, with as many “natural” rates as commodities, there is no single “natural” rate for banks to set their rates at (Hayek earlier rejected using averages) (Sraffa 1932b, 251).

Following Sraffa’s idea, we can describe a generic -year interest rate for commodity :12

\begin{equation}\label{eq:one} r_{c,t} = \frac{q_{c,t}}{q_{c,0}}-1 \end{equation}

where

= the quantity of a commodity , in year

can be further described in real quantities, using zero-coupon bonds and futures contracts: \begin{equation}\label{eq:three} q_{c,t} = \frac{q_{m,0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t})}{F_{\frac{m}{c}, t}} \end{equation}

where

= a present quantity of money

= the -year interest rate on money

= the -year forward price of a commodity, , in money,

The interest rate shows itself through two options: either buying the commodity at spot or loaning money for a year and entering into a futures contract for the commodity, paying using the proceeds of the loan. Both situations result in a present equalization of different quantities of a commodity through time and thus an interest rate.3 Equation \eqref{eq:three} can be input into equation \eqref{eq:one} to form an identity that holds under the law of one price through arbitrage: \begin{equation}\label{eq:four} r_{c,t} = \frac{q_{m,0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t})}{q_{c,0} \cdot F_{\frac{m}{c},t}}-1 \end{equation}

This can be rearranged and expressed differently, depending on whether the starting point is money or a commodity (and is the same equation forming covered interest parity in foreign exchange): \begin{equation}\label{eq:five} S_{\frac{c}{m},0} \cdot (1 + r_{c,t}) = (1+r_{m,t}) \cdot F_{\frac{c}{m}, t} \end{equation}

\begin{equation}\label{eq:six} (1 + r_{c,t}) \cdot F_{\frac{m}{c}, t} = S_{\frac{m}{c},0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t}) \end{equation}

where

= the spot price of a commodity, , in money,

Sraffa (1932a, 50) used bales of cotton in his example without concrete numbers–but his example could be extended hypothetically, to illustrate a commodity rate of interest, where:

- the spot price of cotton is

- the 1-year interest rate on money is

- the 1-year future price for cotton is

Solving the equations for , the 1-year cotton rate of interest in this scenario comes out .

3. Value & Utility Tokens

Sraffa’s elaboration on own-interest rates can be used to think about utility token valuation. The underlying fundamental utilities on a protocol can all conceptually have their own unique interest rates and discount factors, corresponding to the conditions regulating this underlying utility and the protocol where it is distributed. These rates would be formed in the market via spot rates, token interest rates, and futures rates between utility and tokens. In most (if not all) current cases, these rates are not actually possible to calculate, because these futures markets do not exist and thus the argument is entirely theoretical. However, the combination of these features yield a method to think about utility token valuation: \begin{equation} Value_{\frac{u}{tkn},0} = \delta_{u, t} \cdot X_{\frac{u}{tkn}, t} \end{equation}

where

= the discounted value of the future utility provided by a token

= the -year rate of discount for utility

= the time exchange rate,

The utility discount rate is formed by the spot rate, token interest rate, and a futures contract exchanging utility and tokens: \begin{equation}\label{eq:eight} \delta_{u, t} = \frac{1}{(1+r_{u,t})} = \frac{S_{\frac{u}{tkn}, 0}}{F_{\frac{u}{tkn},t} \cdot (1+r_{tkn,t})} \end{equation}

where

= the -year token rate of interest

Thus, as with most things on the market, there is ‘value’ to be found from a utility perspective when the realized future exchange rate, , differs beyond the discount rate implied by the market in the spot and futures rates. If the spot rate is less than the discounted utility projection, the asset is ‘undervalued’ and vice versa. \begin{equation} S_{\frac{u}{tkn}, 0} \lessgtr Value_{\frac{u}{tkn},0} = \delta_{u, t} \cdot X_{\frac{u}{tkn},t} \end{equation}

The over or undervaluation of this utility time trade, depends on the exchange rate as listed today, some forecast on the future value of this exchange rate, and the discount rate used on this utility value. We would note that the the numeraire (standard of value) of these equations is the fundamental utility that is exchanged on a ‘utility protocol’ and is heterogenous, varying widely by protocol, as should the discount rate.

4. Own-Rates of Interest and Opportunity Costs

The discount rate presented allows a relative valuation of utility through time, though any valuation attempt still needs to estimate unknown future parameters. Nonetheless, the presented approach modifies prior token valuation methodologies in discounting the utility directly, without first converting the utility value to an alternative numeraire (such as dollars) before discounting. Will the utility discount rate take the market’s perception of opportunity costs into account, as cost of capital approaches such as the cost of equity, cost of debt, and weighted average cost of capital methods do? This section will present an approach for answering this question, arguing that these costs are taken into account.

The cost of debt for an enterprise is the premium a lender requires for money provided at a present date in exchange for more money at a future one. This money provided is not available to the lender in the interim and is subject to default risk. A prudent lender should take both the opportunity costs of this capital and the risk characteristics of the loan into account in determining the interest rate and thus the cost of capital. Prudent lenders loaning commodities or some utility directly on the market should take similar factors into account in forming a utility rate of interest.

To examine the opportunity costs in detail and reinforce the assertion, the opportunity set of a utility ‘lender’ will be stated clearly. A utility ‘lender’ lends in the underlying utility by lending a token at interest and entering into a futures contract to buy the utility with the proceeds of this loan (or more simply, by lending the utility directly).4 Besides this opportunity, there are a number of alternative available opportunities:

- Consuming the utility today

- Converting the token into something else at spot rates (cash, equities, bonds, bitcoin, paintings, alternative assets, alternative utilities, etc.)

- Hodling or lending the token

By lending utility, a lender is implicitly foregoing the other three opportunities, all of which should be taken into account (but may not be). There is also the risk that the loans and contracts will not be honored in full, which the lender should consider.

Under this model, a profitable (or unprofitable) trade would be expressed in terms of the underlying utility (or token) and arises due a difference in the future exchange rate (utility per token) implied by futures contracts in the underlying utility and the actual exchange rate which materializes in the future. A profitable trade could look as follows:

- Borrower borrows units of some utility , with units of interest at

- Borrower sells units of utility, at spot rates, for utility tokens at

- Borrower lends the utility tokens, until , for units of interest

- Borrower exchanges utility tokens into units of utility, at

- Borrower pays back the utility loan of units of utility, with a gain of units of utility at

If a ‘utility loan’ is carried out by borrowing tokens, converting the tokens to utility today, and going short the futures contract in utility to pay back the token loan, then the net position from the profitable trade, as described above, is just a short position in a futures contract in the underlying utility. The profit or loss is entirely due to a difference in the realized future price and the price locked in by the futures contract.

5. The Equation of Exchange and Alternative Numeraires

The approach presented in the previous section is entirely theoretical–however, for practical estimation, some guideline on estimating the future exchange rate of utility per token, , must be provided. If the equation of exchange is used, with S-curves used to estimate the quantity of utility, , a protocol will distribute in the future, then the explanation provided in section 3 is largely identical to the earlier models of Burniske (2017) and Winton (2017)–the primary difference being that a fiat numeraire is not used.

In Burniske’s and Winton’s models, the dollar utility value per token, prior to discounting, is estimated by , where is the forecasted dollar value per unit of utility, is the total utility units distributed by the ‘utility protocol,’ is the supply of tokens, and is the velocity of the tokens; the numeraire is dollars. In the approach presented in section 3, value is instead expressed in terms of utility per token such that –here is not a dollar value per unit utility, but instead the price level on the protocol: states how many tokens are necessary to exchange into a unit of utility. The numeraire in the approach presented in section 3 is the unique utility on the protocol, which varies by protocol. Each approach’s concept of value, prior to discounting, can be equated to the other by multiplying in (in the case of the model described in the previous section) or dividing out (in the case of Burniske and Winton’s models) the forecasted dollar value per unit of utility, .

Nonetheless, a rate of discount for a token expressed in an alternative numeraire (i.e. dollars) is warranted for valuations in terms of these numeraires. This rate can also be calculated, using the same equations as have been used, as a ‘token-rate of money interest.’ Keynes discussed the concept of a ‘commodity-rate of money interest’ in his own theory of money and interest, building on top of Sraffa’s earlier discussion of own-rates (Keynes 1936, 227). A token-rate of money interest can be calculated as follows (following Keynes’ (1936) notation using ):5

\begin{equation} r_{tkn,t}^{m} = (1 + r_{tkn,t})(1 + a_{t}) - 1 \end{equation}

\begin{equation} r_{tkn,t}^{m} = r_{tkn,t} + a_{t} + r_{tkn,t} \cdot a_{t} \end{equation}

where

= the -year token rate of money interest for token in money

= the -year token rate of interest

= the -year expected percentage appreciation of token in money

We are interested in the monetary discount factor, , for a given token. By multiplying the factor into equation \eqref{eq:five} and rearranging, we get the token rate of money discount for time t: \begin{equation} \frac{1}{(1+ r_{tkn,t}^{m})} = \frac{F_{\frac{m}{tkn}, t}}{S_{\frac{m}{tkn}, 0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t}+a_{t}+r_{m,t} \cdot a_{t})} \end{equation} Following the argument of Keynes, market participants will opt to hold their wealth wherever they think this ‘money rate’ is greatest (Keynes 1936, 227).6 However, in Keynes’ discussion of own-rates he shifts his focus to the fundamental drivers of own-rates, with market prices adjusting to expected appreciation, (Keynes 1936, 226-228). Thus in our own equations, we argue, market spot and futures prices already take the market’s perception of pricing risk and expected appreciation into account and .7 The market discount factor in this situation reduces to: \begin{equation} \delta_{tkn, t}^{m} = \frac{1}{(1+ r_{tkn,t}^{m})} = \frac{F_{\frac{m}{tkn}, t}}{S_{\frac{m}{tkn}, 0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t})} \end{equation}

where

= the -year, numeraire , discount factor for token

If future projections for a given token are to be discounted at the rate based on market perceptions of risk and expected appreciation required on the margin, as is done in a traditional cost of capital calculation, then the valuation formula for a token is as follows:

\begin{equation} Value_{\frac{m}{tkn},0} = \delta_{tkn, t}^{m} \cdot X_{\frac{m}{tkn},t} = \frac{F_{\frac{m}{tkn}, t}}{S_{\frac{m}{tkn}, 0} \cdot (1+r_{m,t})} \cdot X_{\frac{m}{tkn},t} \end{equation}

where

= the time exchange rate,

We need not restrict Sraffa’s own-rates to utility tokens, but they can be used on cryptocurrencies as well (or anything with a spot and futures market). Indeed, Sraffa’s methodology applied to cryptocurrency is not novel: Pelham Smithers Associates (2017) and Mukherjee (2017) followed Sraffa’s idea in November 2017 to calculate annual interest rates of bitcoin, which were estimated at 50% and 57%, respectively.8 This rate could be calculated for any cryptoasset with a spot and futures market; rates at varying maturities can together form a specific ‘cryptoasset term-structure.’

6. Conclusion

‘Utility tokens’ are a financial innovation following Satoshi Nakamoto’s invention of Bitcoin and serving as an exclusive medium of exchange on a protocol which distributes a specific utility. Existing conceptions of ‘utility token’ valuation, such as those developed in Burniske (2017), Winton (2017), and Evans (2018) contain explanations for the drivers of future utility per token, but an explanation of an appropriate discount rate is incomplete. Following Sraffa (1932a) and Keynes (1936), we suggested the concept of ‘own-rates of interest’ can be used to derive the appropriate theoretical discount rate, specifically the utility-rate of interest to discount tokens when a specific utility is the numeraire, and the token-rate of money interest when a reference money is the numeraire. These ‘own-rates’ can be extended to any cryptoasset with a spot and futures market, while varying maturity futures can be used to form a ‘cryptoasset term-structure.’ It was argued that these rates, when calculated from market prices, take the market’s perception of risk and expected appreciation into account, and that there is ‘value’ in a trade when future realizations are greater, after discounting, than spot prices paid.

Addendum

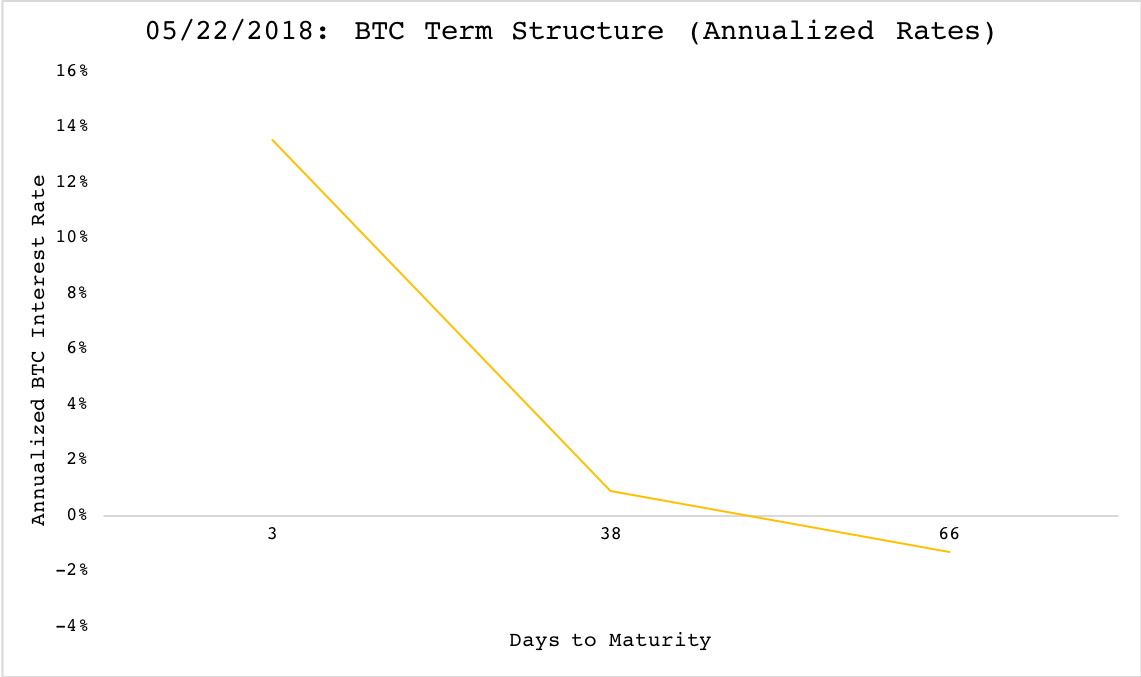

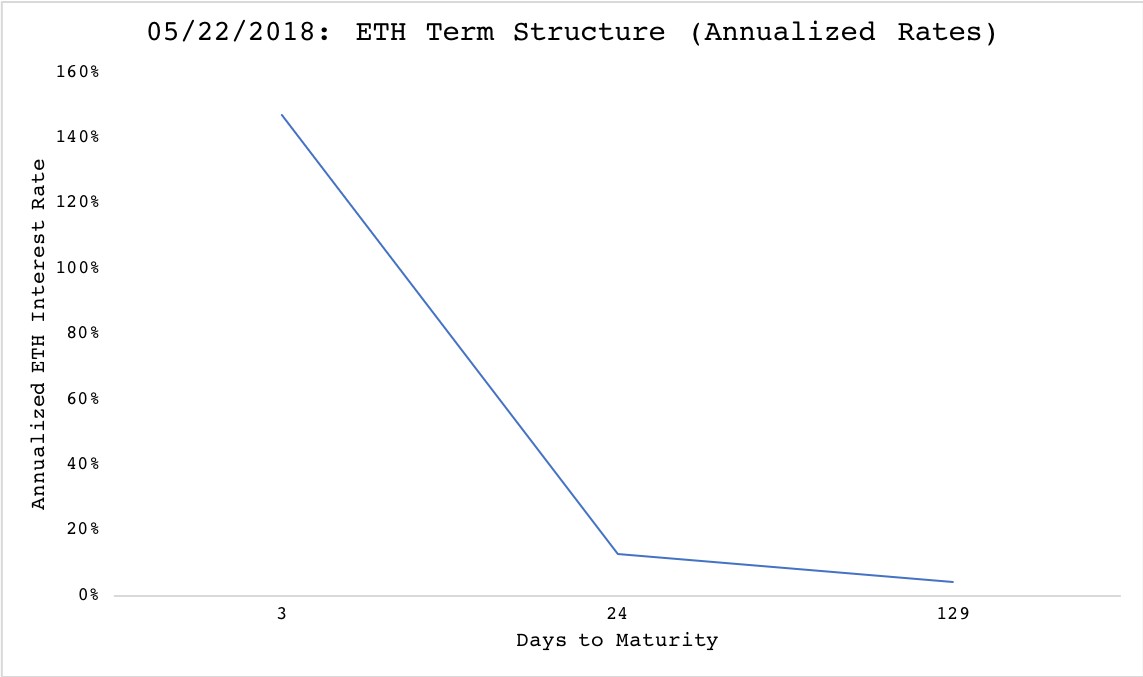

These own rates of interest can actually be calculated in practice for some cryptoassets as Mukherjee did, but for different maturities, forming a ‘term-structure’ for various cryptoassets. Using May 22 pricing data from OnChainFX for spot rates, CME for BTC futures, Crypto Facilities for ETH futures, and the US Treasury for the treasury yield curve (with linear approximations for treasury rates at maturities falling between listed dates) can lead to a quick and dirty approximation of these ‘term-structures.’ Below are the resulting curves:

The sheets file used to calculate the BTC and ETH term structures can be found here. It is interesting that both ‘term-structures’ for BTC and ETH are, as of May 22, inverted. I am still in the process of letting the implications of these curves sink in, in light of the earlier argument made. I’m curious to see what others think, though my instinct would say in the long run the ‘zero-bound’ should still hold–with transaction costs preventing the negative BTC rate from being arbitraged through simply holding BTC.

References

- Burniske, Chris. 2017. “Cryptoasset Valutions.” Accessed February 7, 2018. https://medium.com/@cburniske/cryptoasset-valuations-ac83479ffca7

- Buterin, Vitalik. 2017. “On Medium-of-Exchange Token Valuations.” Accessed March 11, 2018. https://vitalik.ca/general/2017/10/17/moe.html

- Evans, Alex. 2018. “On Value, Velocity and Monetary Theory.” Blockchannel. Accessed March 12, 2018. https://medium.com/blockchannel/on-value-velocity-and-monetary-theory-a-new-approach-to-cryptoasset-valuations-32c9b22e3b6f

- Hayek, Friedrich. (1931) 1967. Prices and Production. New York: Augustus M. Kelly Publishers

- Keynes, John Maynard. (1936) 1964. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Mukherjee, Andy. 2017. “What Keynes Knew About Bitcoin.” Bloomberg. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-11-09/keynes-worked-out-the-bitcoin-interest-rate-it-s-57

- Pelham Smithers Associates. 2017. “The Interest Rate on Bitcoin.” SmartKarma. Accessed May 21, 2018. https://www.smartkarma.com/insights/the-interest-rate-on-bitcoin

- Pfeffer, John. 2017. “An (Institutional) Investor’s Take On Cryptoassets” (version 6). Accessed March 4, 2018. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/john-pfeffer/An+Investor\%27s+Take+on+Cryptoassets+v6.pdf

- Samani, Kyle. 2017. “The Token Velocity Problem.” Coindesk.com. Accessed March 14, 2018. https://www.coindesk.com/blockchain-token-velocity-problem/

- Sraffa, Piero. 1932a. “Dr. Hayek on Money and Capital.” The Economic Journal. Vol. 42, No. 165: 42-53

- Sraffa, Piero. 1932b. “Money and Capital: A Rejoinder.” The Economic Journal. Vol. 42, No. 166: 249-251

- Winton, Brett. 2017. “How to Value a Crypto-asset–A model.” Accessed February 4, 2018. https://medium.com/@wintonARK/how-to-value-a-crypto-asset-a-model-e0548e9b6e4e

- I would also like to thank Cameron Fen, Frank Hofmann, Johannes Smit, and Paul Eusterbrock for reading drafts of this.

Footnotes

-

We can describe a more general form of an n-year interest rate, f-years forward: . In the common case where a commodity (usually money) is lent today to be paid back at a future date, . The more general form can be used to create a ‘term-structure’ of commodity interest rates and forward lending rates. ↩

-

Under this equation the geometric average annual yearly rate would be: ↩

-

A commodity can be ‘lent’ through selling it at the spot price, putting the proceeds into bonds paying money interest of , and going into a futures contract with the money proceeds at a price of . ↩

-

A utility borrower would do so by borrowing a token with interest, converting the token to utility at the spot rate, and going short a futures contract for utility to pay back the token loan. ↩

-

Keynes (1936, 227) approximates a generic commodity-“rate of money interest” as . ↩

-

Keynes does not specifically mention risk in this section, but we would add the market’s perception of risk is considered in forming this choice. ↩

-

Keynes’ (1936, 226-228) decomposition of own-rates using their fundamental drivers (, , and ) instead of using market prices creates a non-zero , which together form market own-rates of money interest. ↩

-

Pelham Smithers Associates’ (2017) report is not an open report and thus Mukherjee’s reference to their article was used. ↩